Rendering in 3D is more complicated than in 2D. Some knowledge of how your engine renders its scenes can make it easier to know why your game slows down.

Knowing where you can compromise to draw out more performance is important. In this guide, we’re looking at the tools you have to understand why your framerate goes down and what you can do to bring it back up.

The graphics Monitor

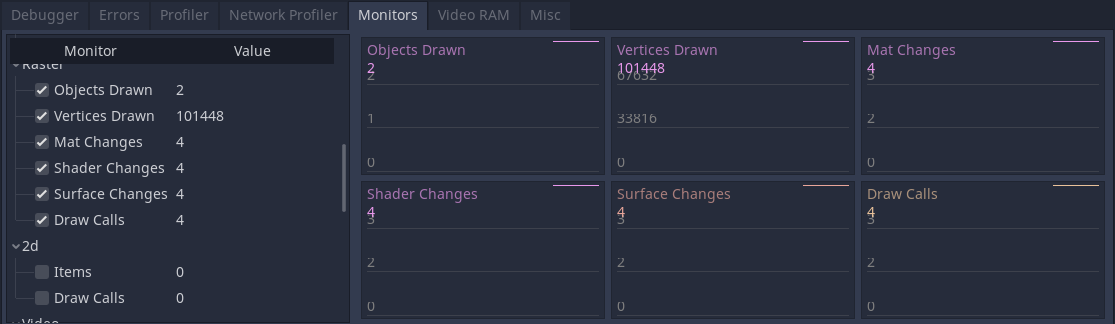

In the debugger bottom panel, the Profiler measures your functions’ execution speed while Monitors reports on individual systems in Godot, including the 3D renderer.

While the profiler reports execution time in milliseconds, the monitors display task counts.

For 3D, the monitors relevant to rendering are under the Raster category: objects drawn, vertices drawn, mat changes, shader changes, surface changes, and draw calls. You use these statistics to figure out what is slowing the rendering down.

Here’s a description of four monitors that can have a significant performance impact:

- Mat changes are when the CPU tells the GPU to replace a material with a new one.

- Shader changes are when you change shader code.

- Surface changes are when you update the world’s geometry.

- Draw calls are the CPU telling the GPU to render something.

They involve sending instructions from the CPU to the GPU, which is slow. Godot tries to optimize the render to make fewer of these changes as possible.

As you go optimizing your 3D scenes, you should have two targets in mind at all times: a target frame-rate, and target hardware. On mobile, it’s common to aim for 30 frames per second. In comparison, for virtual reality, you need to render at least 90 frames per second at all times to avoid causing motion sickness.

If you want your game to run on slower machines than your workstation, consider gaining access to one and testing your game on it directly.

Optimizing draw calls and state changes

The GPU is an excited hunting hound held back by a harness. It’s always ready to go as fast as it can. But before that, the CPU has to tell it what it’s about to draw, the data to use, and in what order. The more preparation work the CPU has to do, the longer the GPU waits and the lower the framerate.

The monitors we saw previously are the main kinds of information sent from the CPU to the GPU. Sending that data is slow, so minimizing that preparation time is vital to keep the frame rate high.

Here are some common considerations for speeding up a 3D scene.

Reducing draw calls by optimizing meshes

When the GPU draws something, Godot provides it with the 3D model’s vertex data to draw. Ideally, it draws as much of the model in one shot as possible to reduce the amount of back-and-forth with the CPU. But in Godot 3.2, this batching of draw calls isn’t built-in; it is something you have to make happen. Suppose you have a house made up of walls, windows, a roof, a floor, a door, and a chimney, and each of those objects is a different surface. In that case, it can cause ten or more draw calls, repeated for every copy of the house. In your 3D software of choice, try to combine such meshes into one surface.

For meshes that look the same except for where they are and which way they are facing, consider rendering them with a MultiMeshInstance. This node type takes one mesh and draws it many times in a single draw call by assigning each instance a unique 3D Transform and some custom data. It takes some code to set up, but drawing an enormous city full of similar-looking buildings runs a lot faster that way.

Reducing draw calls with fewer lights and shadows

Godot’s lights behave differently depending on their type.

Local light sources like Omni and spotlights, without shadows, add zero draw calls. However, an object has a maximum of 8 light sources and which lights it uses depends first on their order in the scene tree, then their distance to the object.

An Omni or spotlight with shadows adds four draw calls per light per object whenever the light or the object updates. That means shadows are free so long as the light and objects that cast shadows do not change.

Directional lights add one draw call per light per object instance. However, the first one replaces the default light in the world environment and comes at no additional performance cost. Casting shadows with directional lights adds four draw calls per light per object. Unlike with Omni and spotlights, directional shadow maps redraw every frame.

One more way to have great lighting on your static scene is to use Baked Lightmaps, either using Godot’s system or an outside one. It can give great results, but lightmaps are pre-rendered and do not change at runtime.

Reduce material and shader changes

Godot does its best to sort objects and minimize state changes like switching materials and shaders. But this system has its limits. You can help it by giving the same material instance to more objects. For example, small objects could have their UVs occupy different places but share the same texture map. That way, they can share one material instance.

The same applies to shaders. Use the same shader resource on multiple objects. If two shaders have the same code, but they’re instanced separately, Godot compiles and treats them individually.

The graphics card’s amount of work and fill-rates

Once the CPU gives the go-ahead, the GPU can do all the work it needs to do on its to-do list. But even though it’s blazing fast at its job, it still has limits. Once you’ve done as much as you can to lower the amount of work the CPU has to do before the GPU can do its job, you have to look at the GPU’s job and see if there are any gains you can have.

Reduce overdrawing

Godot does not draw objects outside the bounds of the camera (frustum culling), but it does not do tests to check whether objects are behind walls. Overdrawing means drawing objects despite them being behind other objects and, as a result, not visible.

Try to design your levels and scene trees so that you can toggle visibility on large portions of your level when you know it will be invisible. When the player steps into a closed room, automatically close the door behind them and hide the rest of the level until they open the next door. Place walls so they cover objects outside them and hide everything the player can’t see.

Reduce the number of vertices to draw

You can start by removing vertices that you cannot see. If you have a house that the player will never be able to look behind, you can remove the floor and back walls. You don’t need an interior if the player cannot look inside.

If the player can see the whole object, but it’s far away, don’t be shy about lowering the details. Many video games have hilariously under-detailed birds, but they are so far away and so small and moving so fast that the effect is still convincing

Lower the number of vertices you use on spaces that don’t need the vertices. If you have a large wall, it probably does not need to have 300 edge loops running. Bake details down into a normal map instead of individually modeling bricks.

Reduce the amount of pixel and texture work

GPUs have two fill rates when it comes to pixels: the pixel fill rate and the texel fill rate. The pixel fill rate is the amount of the pixels it’s able to push to the display. Lowering your game’s internal resolution and scaling up is one way to lower the work needed by the GPU. Games on lower-end hardware like consoles frequently downscale viewports to maintain the frame rate.

The texel fill rate is the number of pixels the GPU can apply to a fragment by reading textures and sampling them along UVs. Using fewer and smaller textures minimizes the work the GPU has to do, which is vital on low-end hardware.

Optimize shader code

When writing shader code, expensive calculations can happen on the vertex shader instead of the fragment shader. The vertices’ values then are interpolated across the surface using a varying variable.

If you have a lot of data you can pre-calculate, consider encoding it into a texture. You can then look up the value with a call to texture instead of calculating it on the fly per fragment.

Ensuring your code runs as fast as possible and does not use dynamic branching can give you performance gains.

Optimize for consistency

As a final consideration, if you cannot hit your target FPS on your target hardware and you’re getting out of budget, lower the target FPS and optimize to stay there. A full resolution constant 30 FPS game will feel better than a game that runs somewhere between 35 and 50 FPS, dipping up and down as it plays.

Made by

Our tutorials are the result of careful teamwork to ensure we produce high quality content. The following team members worked on this one:

Senior Developer

Founder